On Sunday, December 7, 1941, Aiko Yoshinaga, a 17-year-old student at Los Angeles High School, was being driven home from a party with classmates when she heard a shocking radio report that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor. At a young age, Aiko immediately recognized that if the United States declared war on Japan, their Japanese immigrant parents, who were legally prevented from being naturalized, would not only be viewed as foreigners, but as hostile foreigners.

As a US-born citizen, Aiko did not think she had cause for concern. She thought she was protected by the US Constitution. Together with my grandparents and parents, she would soon find out how wrong she was. My father, then a 14-year-old freshman at Huntington Beach Union High School, later recalled, “People couldn’t or wouldn’t differentiate between Americans with Japanese parents and Japanese.”

A boy, whose family is being admitted to a detention center, waits for his parents in San Francisco on April 6, 1942, while a military policeman watches him.

(Associated Press)

The attack on Pearl Harbor heightened the anti-Japanese sentiment that had existed since the first wave of immigration from Japan in the 1880s. Against a backdrop of decades of discriminatory policies, the Japanese-American community was vulnerable as a horrified and angry nation mistook anyone who looked like the enemy to be the enemy.

Even before the attack, high-ranking officials in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration and military leaders assumed that the Issei, or first-generation immigrants and the Nisei, their American-born children, would defend US interests in the event of war, despite intelligence reports. who refuted these claims. Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, who would head the Western Defense Command during the war, said publicly, “A Jap is a Jap – it makes no difference whether or not he is an American citizen.”

Paul Webb, then director of Los Angeles High, decided that Aiko and the other 14 Nisei seniors would not get their diplomas because “your people bombed Pearl Harbor.”

Shigeko Kitamoto and her children are evacuated from Bainbridge Island, Washington on March 30, 1942. One child is being held by a member of the military guard who oversaw sending people of Japanese descent to desolate “camps” in California.

(Associated Press)

In January 1942, Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron was among the West Coast mayors who directed a racist choir to remove the Japanese who lived in their areas. League of California Cities officials, heads of key industries – particularly defense companies and large agricultural companies – and journalists joined in.

US MP Leland M. Ford, whose district also included Santa Monica, was the first member of Congress to advocate the mass incarceration of “all Japanese, citizens or not.” He even advocated that they could prove their true loyalty and “patriotic” by voluntarily detaining themselves.

On February 19, 1942, a little more than 10 weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 calling for the detention of approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent – two-thirds of whom were Nisei American citizens – as a “military necessity. “Soldiers armed with rifles and bayonets were removing men, women and children from their homes in California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona.

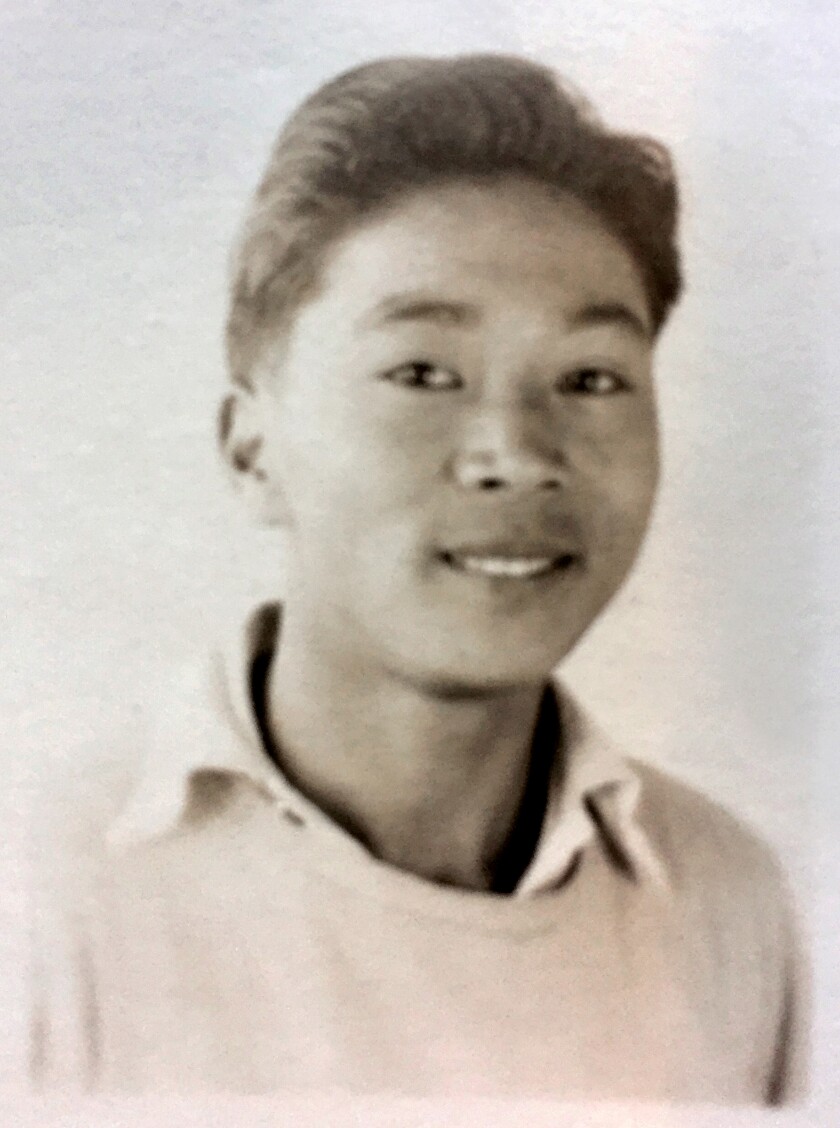

Hiroshi Kamei, the author’s father, as appears on the War Relocation Authority file in the National Archives when he was about 15 years old and incarcerated in Poston, Arizona, in 1942.

(Family photo)

In the short term, they had to leave their shops, farms, jobs, education, even their pets behind. They were only allowed to take with them what they could carry. They had to sell, store, or give up the rest of their property. My father’s farming family had to leave several acres of celery that were ready to be harvested. My father, Hiroshi Kamei, would call it “my family’s greatest economic loss.”

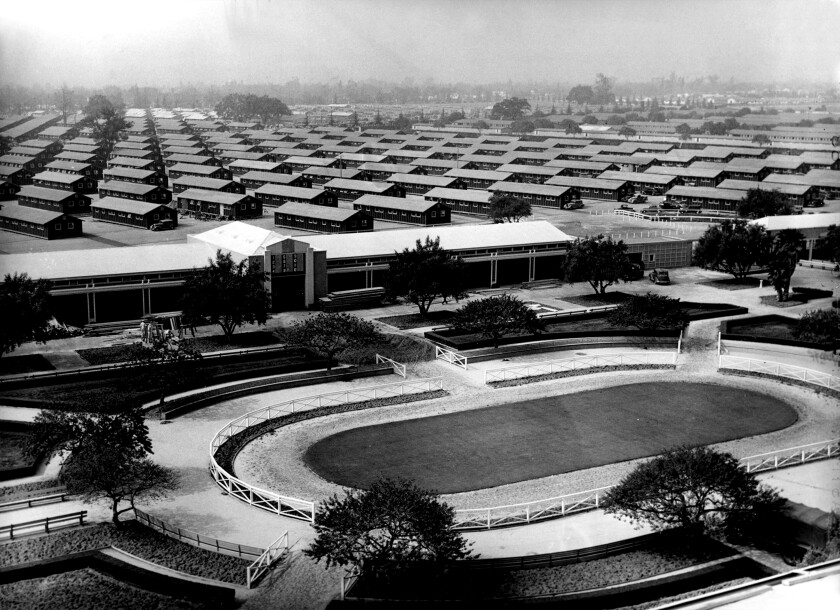

That spring, Japanese Americans were taken to temporary detention centers euphemistically called “Assembly Centers,” including one on the Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia. After my mother Tami Kurose, then 14 years old, arrived there with her parents, they considered themselves lucky to have to live in barracks and not in horse stables that stank of manure.

Later that summer, incarcerated Japanese Americans were relocated to one of 10 newly constructed locations in desolate locations under the jurisdiction of the War Relocation Authority. When Aiko realized how isolated the Manzanar prison camp was in the Sierra Nevada, she said she thought, “This is where they are going to shoot us.” She feared that “no one would tell the difference” if the government killed them all there.

The Santa Anita Circuit in Arcadia on April 3, 1942, after it had been converted into one of the temporary detention centers euphemistically called “Assembly Centers”. Japanese Americans lived in barracks that were built in the parking lot and in horse stables.

(Associated Press)

Aiko, my parents and their families, and the other Japanese Americans imprisoned, would remain behind barbed wire and in harsh conditions for the duration of the war. Even as the war drew to a close in 1944, FDR refused to close the so-called camps until he was re-elected in November.

For decades after the war, those detained focused on rebuilding their lives and repressed feelings about their illegal imprisonment. My father remembered being “too busy” trying to recover from the devastating effects of imprisonment to be bitter. In the late 1960s, while living in New York, Aiko became involved in civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements that challenged government policies. Inspired by the activism of others, she was motivated to investigate the causes of the imprisonment.

Some of the first Bay Area residents to be incarcerated at the converted Tanforan, California, circuit on April 28, 1942.

(Clarence Hamm / Associated Press)

Using research techniques she developed and in collaboration with lawyer and law professor Peter Irons, Aiko began to search thousands of documents in the national archives in the late 1970s. She would play a vital role in documenting government wrongdoing, which included never suspecting Japanese Americans of disloyalty, knowingly upholding lies to justify imprisonment, and covering up attempts by Justice Department officials to tell the truth.

The evidence formed the basis of the 1983 report “Personal Justice Denied,” the government’s official study of the detention of people of Japanese descent during World War II. It concluded that Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity, but was due to racial prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership. His recommendations – an official apology to those imprisoned and symbolic reparations for those still alive – weren’t made until 1988, when the Civil Liberties Act was passed.

Residents of Bainbridge Island., Washington, pass through a ferry dock on March 30, 1942 en route to their incarceration in California.

(Associated Press)

In 1989, Los Angeles High attempted to make amends by issuing Aiko and her Nisei classmates the diplomas they were denied in 1942. For her role in clearing the record, the Japanese American National Museum honored Aiko with the Award of Excellence Gala in April 2018 in recognition of her service to democracy. She died three months later at the age of 93.

Today, as violence against Asian Americans has escalated into an “epidemic of hatred,” the 80 is judged to be “American enough” based on our origins and looks. President George W. Bush once said of imprisonment: “Sometimes we lose our souls as a nation. The idea of ’all equal under God’ sometimes disappears. “

The annual attacks on Pearl Harbor arouse complex emotions among those who had previously been arrested and their descendants. They have joined to honor those who lost their lives in the December 7th attack and to pay tribute to the Nisei soldiers who valiantly demonstrated the loyalty of Japanese Americans in battle. But my father, who died in 2007 at the age of 79, prepared for the rest of his life every December 7th for the rest of his life for the anti-Japanese backlash that inevitably occurred on every anniversary. He was always eager to see that date come and go.

Susan H. Kamei is a senior lecturer in the history department at USC Dornsife. She is the author of When Can We Return to America? Voices of the Japanese-American imprisonment during World War II. “

Comments are closed.