As president of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Joel Wachs often receives messages regarding the licensing of the iconic pop artist’s name and image. So when director Paul Thomas Anderson reached out, Wachs assumed Warhol was being featured in a new movie.

“No, no. It’s you I want to talk to,” Wachs recalls Anderson telling him during a subsequent phone call. “It’s your name I want to use.”

Wachs has lived in Manhattan since 2001, but he spent three decades as the City Council member for the same Los Angeles district where Anderson was born and raised. In writing “Licorice Pizza,” a rapturously told coming-of-age tale set in the San Fernando Valley of the early 1970s, the filmmaker incorporated many of his memories of growing up in Studio City, from beloved Valley landmarks like Tail o’ the Cock and Papoo’s Hot Dog Show, to the local politician whom Anderson’s parents championed and voted for — and whose office he walked past every morning and afternoon, to and from school.

Anderson told Wachs that if he was uncomfortable being identified in the movie, the character could be renamed. Of course, the director was hoping Wax would say yes. “It mattered to me,” Anderson says in an email interview with The Times. “He’s an indispensable part of Valley history.”

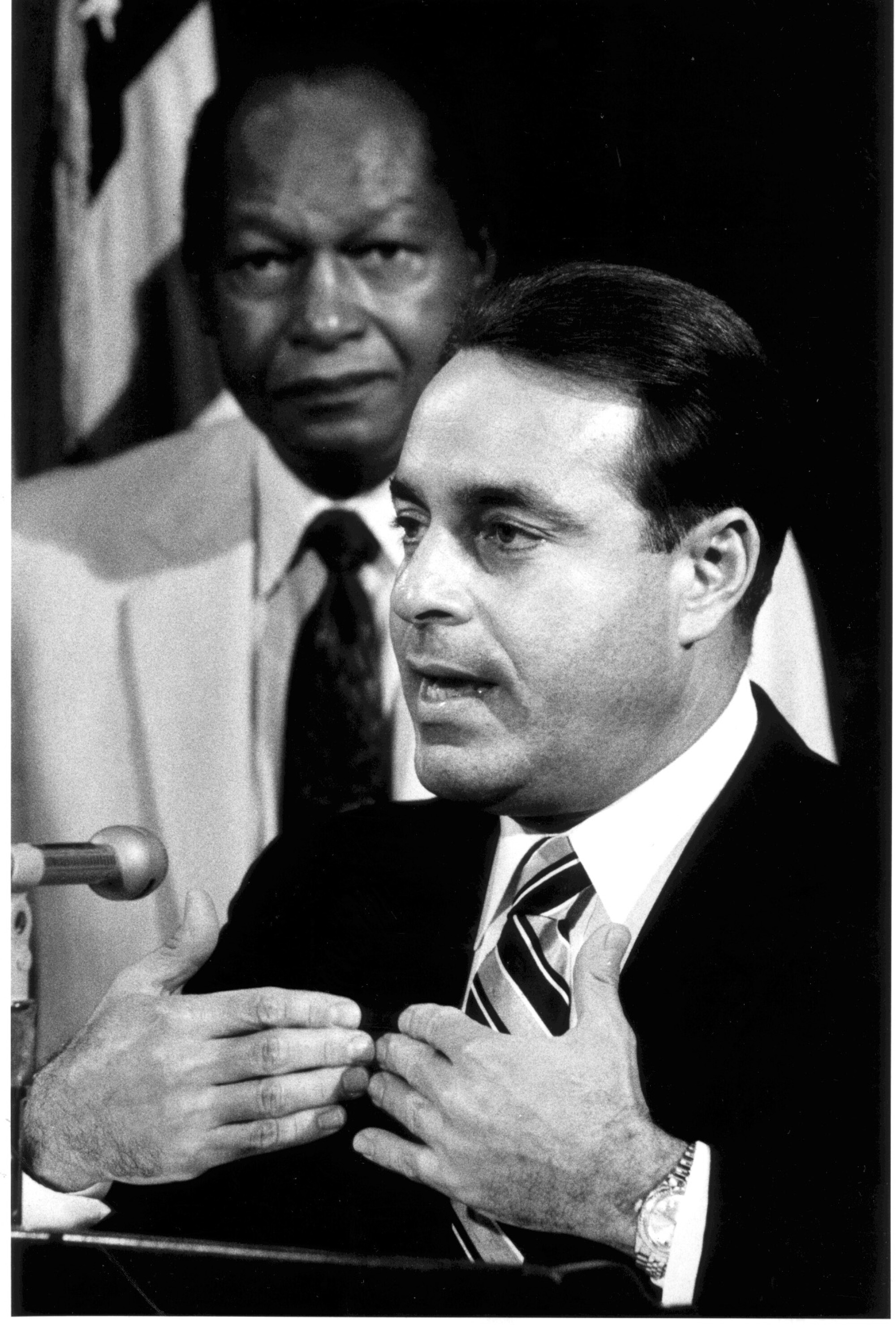

Joel Wachs, left, with then Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan in Jan. 2001.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Anderson got the go-ahead, but only after Wachs read the script for “Licorice Pizza” and got to the part most relevant to him: In it, 20-something protagonist Alana Kane (played by Alana Haim) is searching for direction in her life and decides to campaign for an earnest, young and closeted gay city councilman who is running for mayor.

“I thought, ‘There’s only really one human being who was a city councilman in the San Fernando Valley in [the ‘70s] who was running for mayor,’” Wachs says. “Anyone who wanted to find out could easily identify it as me. So I thought, ‘Why not?’”

Unlike Anderson, Wachs wasn’t native to the Valley ZIP Code. He was born in Scranton, Pa. When he was 10, his father moved the family to the Vermont Knolls neighborhood in South LA and opened a string of women’s ready-to-wear clothing stores. During this period, Wachs went to high school with future dist. atty Gil Garcetti and got involved in student government. “He was the A-12 class president and I was a B-10 senator,” Garcetti says. “So that’s how I got to know him. … He had he gift of gab.”

Wachs’ journey to the Valley began after he collected a law degree from Harvard and landed a job at a downtown Los Angeles firm as a tax lawyer. In 1971, living in a rented apartment above the Sunset Strip — which, like portions of the San Fernando Valley and the Santa Monica mountains, fell into District 2 — Wachs aimed his sights on a Los Angeles City Council seat.

Wachs’ campaign was a family affair: His mother ran his base of operations while his father stumped for him by standing in front of Gelson’s and Ralphs supermarkets holding a sign that said, “Vote for My Son, Joel.” Wachs took a hiatus from work and spent five months knocking on doors throughout the Valley, seven days a week. When he won the election, he was 32, the youngest member of the 15-member body. He decided it was time to move over the hill to the valley.

Joel Wachs with Mayor Tom Bradley after a law the council member authored to protect the civil and human rights of AIDS victims was signed into law on Aug. 16, 1985.

(Con Keyes/Los Angeles Times)

Wachs says Anderson was open to receiving notes on the script for “Licorice Pizza.” “Some he took, some he didn’t,” says Wachs, adding that, by and large, the big-screen Joel Wachs portrayed by Benny Safdie was remarkably similar to the real-life ’70s era Joel Wachs. This, he learned, was due to the fact that Anderson was close friends with film and television producer Gary Goetzman, the character upon which “Licorice Pizza’s” leading man Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman) is based. Goetzman was in his teens when he energetically burst into Wachs’ life. “We were looking for as many volunteers as we could get and he had all these great ideas and he wanted to make a commercial with me,” says Wachs. “I said, ‘We don’t have any money.’ He said, ‘I’ll take care of it all.’”

Of course, there’s a scene in “Licorice Pizza” documenting the filming of the TV commercial. How could there not be? There’s something inherently funny about a new politician putting his public image into the hands of a nervous adolescent. Set in the Santa Monica mountains, the scene features Joel Wachs delivering anti-developer promises as Gary Valentine films and Alana Kane directs. According to Anderson, this moment was flagged by Wachs as erroneous — he told Anderson that Goetzman also directed. “I had to correct him, and say, ‘No, believe it or not, it was Jonathan Demme,’” Anderson says in an email, referring to the Oscar-winning “Silence of the Lambs” director who had yet to make a feature at that stage of his career.

Wax had other notes for Anderson. “I’m not disorganized,” Wachs told him in reference to an exchange of dialogue where the candidate admits to Alana that he’s absent-minded. There was also the matter of the secret boyfriend who feels attention-starved. According to Anderson, “First off, he said it was completely implausible to be a city councilman and run for mayor and have a boyfriend at the same time! The moment Wachs saw that there was a love interest in the film for him, he wrote in the margin of the screenplay, ‘Yeah, right!’”

Benny Safdie as Joel Wachs and Alana Haim as Alana Kane in “Licorice Pizza.”

(Metro Goldwyn Mayer Pictures Inc.)

Wax knows that “Licorice Pizza” isn’t a biodoc about him. Speaking by Zoom from his elegantly appointed, white-walled Manhattan apartment, Wachs, who came out publicly in 1999 at age 60, still feels compelled to explain why, as a public figure back then, he felt he had to keep his true self hidden . “The suppression was enormous,” he says. “I knew a lot of gay people in the industry — the most well-known ones like Rock Hudson, but many lesser-known people as well. Everyone in those days, people were hiding, because the consequences of coming out would be so great. So much has changed since then, for the good. I’m actually glad that [Anderson] did use my name, because now we can have these discussions.”

Still, a guy’s got to have a life. Wachs and his friends would meet for dinner at restaurants like West Hollywood’s the Carriage Trade, where one could sneak in unseen through a side alley. Or — his favorite — the Golden Bull steakhouse in Santa Monica Canyon. His fear of people putting two and two together in certain public spaces, however, didn’t stop him from patronizing Oil Can Harry’s, the venerable gay nightclub on Ventura Boulevard. His cover, he rationalized what that he was a public servant.

“I’d say, ‘This is a business in my district,'” says Wachs, with a light shrug. “’I have to see what it’s like and support it.’”

Back in the early ’70s, when Wachs was door-knocking and getting to know his constituents, he noticed that an alarming number of people seemed to be at home in the middle of the afternoon. It didn’t take long for wax, who is chatty, to find out that he was meeting grips, set designers and stagehands, out of work during a time when Hollywood was backing away from big-budget epics. Most of them were struggling to make ends meet. He made it one of his missions to help find federal and local resources for unemployed industry workers as well as people in the arts.

“Not only do I love the arts personally, but it’s important to the city,” says Wachs. “Creativity is one of the main resources in Los Angeles.”

Former Los Angeles City Council member Joel Wachs in his art-filled Manhattan apartment.

(Jesse Dittmar/For The Times)

On the wall just behind wax hangs a piece by Betye Saar, the famous Los Angeles printmaker and assemblage artist. Since the mid-’70s, Wachs has devoted a quarter of his paycheck to buying art. He has donated 100 works to MOCA and he estimates that 75 have been given to the Hammer Museum. “If, God forbid, a big red bus comes by,” says Wachs, “MOCA gets all the paintings and sculpture and the Hammer gets all the works on paper and drawings.”

Most of his major collection is stored in Los Angeles. But despite having lived in Manhattan for 20-plus years, there are things about the Valley that make Wachs’ voice fill with longing.

“I still miss the Smoke House,” he says of the throwback red-booth restaurant across from Warner Bros. studios. “Oh my God, I want their garlic bread. It was so good.”

Comments are closed.