If things had turned out differently 125 years ago, all those monster cargo ships now anchored off San Pedro would instead wait on the sandy beaches of Santa Monica.

In the Battle of the Great Free Port, two California oligarchs and their loyalists fought over where the federal government would invest their money in LA’s first industrial port. It was like a bearded, Victorian version of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk racing each other into space, even though there was enough room for both of them; there would never be a port of San Pedro and Santa Monica.

The paradox of industrial Los Angeles County is that it thrived even though it did not have a traditionally navigable river or natural harbor. San Diego has a natural harbor. San Francisco has a peach of one. But Los Angeles only had beaches and cliffs and mud flats and marshes that stretched from Point Dume in Malibu to below Long Beach. But LA never allowed nature to interfere with self-invention.

Today – at least if the supply chain is not throttled – 40% of all freight going to the USA comes through the partner ports of LA and Long Beach, the largest port operator in North America.

But in the 1890s, when LA’s spurt of growth drew thousands of new residents from the rest of the country by train and millions of plank yards of lumber to house them – mostly from the Pacific Northwest – LA’s ports and harbors struggled to stay high.

That’s not to say that boats and ships were alien to LA waters. Native Americans were legendary at navigating the coast. In October 1542, the first known European to meet California, the explorer Juan Cabrillo, came ashore in a longboat and stayed around long enough to call the place “Bay of Smoke” because of the haze he encountered – Welcome to LA! – and sailed further north, where it completely overshot San Francisco Bay. Six decades later, the Spaniard Sebastian Vizcaino was sent out to check out potential ports, and voila, “San Pedro Bay”.

Explain with Patt Morrison LA

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison explains how it works, its history and culture.

It wasn’t until the Spanish missions were built in LA in the 18th century that the need for a functioning port became apparent, but Spanish trade restrictions turned the Los Angeles coastline into a smugglers’ paradise. The first American ship to enter the port around 1805 made a fine, bold catch that illegally traded Californian otter skins under the noses of the Spanish authorities, who anyway had no garrison in San Pedro. When Mexico gave Spain the boot and California took over, the trade in “California dollars,” cattle hides, was legalized and regulated – and its rules were regularly disregarded by ship captains who, in return, brought the world’s luxury to California.

The writer Richard Henry Dana worked as a seaman during these years and wrote about the hides that were carted to the coast from the “Pueblo” to bring them to the waiting ships in front of San Pedro, “We all agreed that it was the worst place was “. We hadn’t seen it before, mostly to get off the skins ”and worse, to fetch goods like sugar from the landing craft and over the“ green, slippery rocks ”. … At night we went on board after the hardest and most unpleasant working day behind us. We were kept in this way for several days, until we brought forty or fifty tons of goods ashore and about two thousand hides on board. “

Far from being an ideal port for a future city.

When California became a state in 1850, Yankee businessmen went to this new American frontier, and none was more energetic than Phineas Banning, the “father of the Port of Los Angeles,” a Delaware man whose red braces made him a distinctive figure Harbor. He arrived a year after the founding of the state and immediately began moving more goods ashore and ashore faster. He bought coastal land, co-founded the city of Wilmington, started a stagecoach and wagon service to connect downtown LA to the distant port, and also started the first railroad service in Southern California in 1869. (That would in time be adopted by Southern Pacific, the grasping, squeezing “octopus” railroad monopoly of California lore, and soon be taking the stage in the port drama.)

Why, you might ask, should the Port of Los Angeles be down in San Pedro when there was a pretty good beach nearby, in Santa Monica?

The fact is that neither location was a sailor’s idea of an ideal port, but by 1890, when the population and reputation of the city were muscular, the showdown between the two locations quickly came about.

San Pedro had a decade-long head start when Southern Pacific, led by Collis P. Huntington – one of the Big Four California titans who made their first fortune in the gold rush by selling mining equipment at hefty markups to the barrage of 49ers sold – decided that the port should be in Santa Monica, where shipping happens to be controlled solely by the powerful SP, along with a large piece of coastal land.

Huntington’s was not used to being thwarted, and local authorities, the state legislature, and Congress were populated with men committed in one way or another to “Uncle Collis”.

The seven-year battle over the harbor turned out to be not a battle between David and Goliath, but between Goliath and Goliath. The Times editor, the equally unruly Harrison Gray Otis, used his inky black pulpit to forge a unit fabulously named the Free Harbor League, and gathered the city, its business and citizen leaders against Huntington, a man, the Otis called “the old sinner” in print.

And Huntington, in the midst of seven years of state study and debate over funding a breakwater for a new port, made a costly, calculated setback.

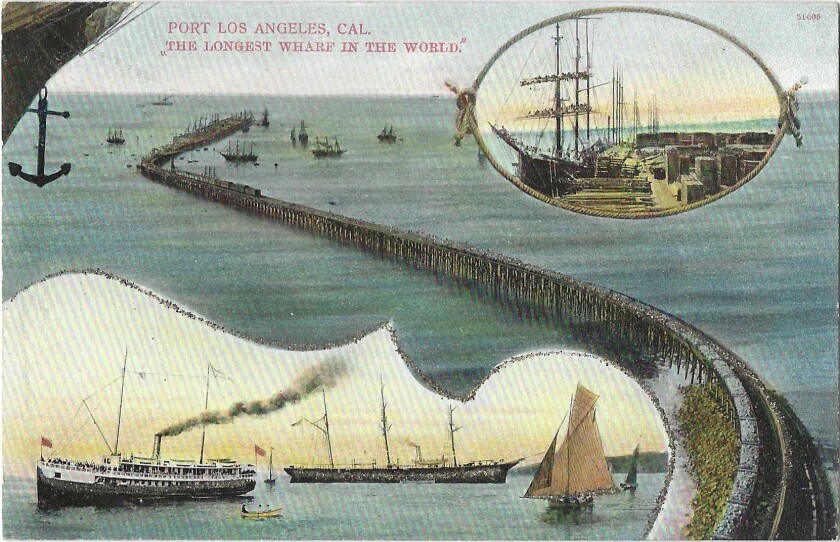

From his property in Santa Monica he built an almost comically long pier into Santa Monica Bay: 4,700 feet, which he named “Port Los Angeles” to add to the grandiose factor. It also passed Long Wharf and Mile-Long Pier, hauling cargo and passengers to show that it was possible.

Collis P. Huntington’s Long Wharf extended 4,700 feet into Santa Monica Bay.

While this was going on, Congress had entered the battle. His vote to fund a breakwater would essentially determine whether San Pedro or Santa Monica would be the port of LA. Against Huntington’s elected loyalists stood Stephen M. White, a young lawyer and Democrat, but the Republican Otis was his friend – and his client.

Before his port exploits and as a civil servant and US senator, White had defended the shameful Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and put it on record in 1893 with ugly comments about the Chinese as “an alien race” and worse.

In May 1896, for three days, White disassembled Huntington’s case, compiling the government’s own studies, ancient sailors’ assessments, and popular opinion that Santa Monica was a poor choice in almost every detail. A west bank like Santa Monica was more exposed than a south bank like San Pedro, which was pampered by Santa Catalina Island, whose lapping waves, White assured the Senate, were so calm that “there was no trouble gives normal weather with an ordinary row boat “operated by a lady or sturdy boy” to navigate them, and so the waters of San Pedro are calmed by it.

White revealed that an allegedly “disinterested” party was a Huntington’s agent. The approval of millions to build a breakwater – a foundation structure required for a port – for Santa Monica, he explained, “will be a donation of $ 3,098,000 to a private company” – Southern Pacific – and “a Public outrage ”.

White won the day. And while Huntington gritted his teeth, Otis cheered in the print: “THE EAGLE SCREAMS: SAN PEDRO SELECTED AS THE PUBLIC PORT …

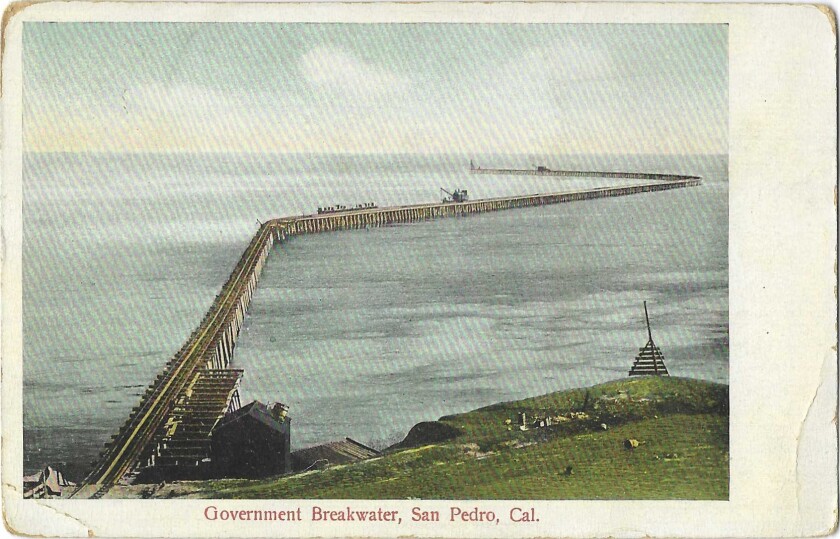

Every port needs a breakwater – LA port can be seen here on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

In 1899, crowds gathered to watch work on the breakwater off San Pedro begin and the port dredged and improved over decades. Together with the port of Long Beach, founded in 1911, it became the largest in North America and indispensable during the years when California was the country’s leading oil producer.

Long Wharf, the world’s longest boardwalk, was dismantled in 1933 and only one historical clue points to its history.

The US military found the new port locations useful. For 60 years a military reserve loomed on the cliff above San Pedro, mostly known as Fort MacArthur, and from 1932 to the 1990s Long Beach was the home port of the Pacific Fleet.

Some of you may have cleverly noticed the fly in the ointment. San Pedro and Wilmington were their own cities that were not part of Los Angeles. Then how could they be the port of Los Angeles if they weren’t in Los Angeles?

LA’s solution was to annex the two cities over a land navel about 25 kilometers long and sometimes only half a mile wide that ran from the southern city limits to Wilmington and San Pedro – the “city strip” or “lace strip”. . “

Voters in LA and the City Strip voted for the idea in 1906, and three years later Wilmington and San Pedro voted to give up their independent city status and join Los Angeles.

Countless stories can be told about the port, its surprising ethnic mixes, reports about its small islands, home to a flourishing Japanese fishing community before World War II, today the location of a federal prison whose inmates were gangsters – including Al Capone – serial killer Charles Manson and the LSD enthusiast Timothy Leary.

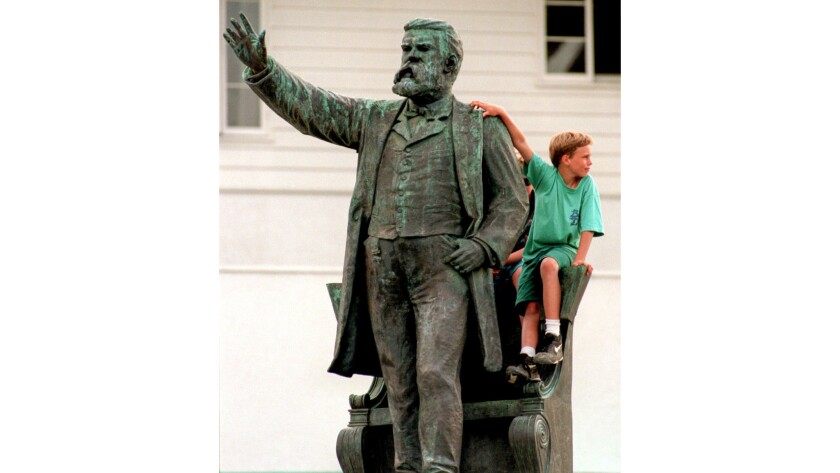

July 20, 1994: Patrick Rozelli, 11, hangs from the Stephen M. White statue overlooking Cabrillo Beach in San Pedro.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Stephen White was enough for one term in the Senate. He died in 1901, not yet 50 years old. In 1908, a bronze version of him was erected in the LA Civic Center, with its outstretched arm more or less pointing towards the harbor, but more like a man calling a taxi.

Eighty years later, the construction of Metrolink forced it to move to a warehouse, but San Pedro came to the aid of its savior Senator, and the statue now stands near the entrance to Cabrillo Beach. For now.

Comments are closed.